“There is no life without death.”

- Kathryn Kupillas (Inner Vision Psychotherapy)

In Summer Wagner’s photo Strength, a young woman holds up a short blade to the neck of a passive fawn. When you look at the piece, what do you see? What story emerges?

I happened to see the piece as it was first posted on Twitter and Instagram by the artist. As one can expect from the internet, there were some angry reactions to it. Some people thought they were witnessing a photograph of a woman in the process of killing a real fawn (it’s taxidermy). Others knew this wasn’t a ritual killing caught on camera but were still angry at the depiction of violence against animals. People tagged PETA in the comments.

The lion is a symbol of raw strength and power. But in the classic strength tarot card, a woman stands over a lion, caressing his head and face. The woman is in a white dress and adorned with flowers suggesting that she subdued and harnessed the power of the lion with care and cooperation, rather than control or force. The card is a symbol of inner strength, courage, and compassion.

In Summer Wagner’s version, the image also uses a young woman hovering over an animal. However, the image is edgier and takes on the stylistic vision that is typical of Wagner’s work. Instead of a dress, we get a tank-top with jeans, which works works to place spiritual motifs into our contemporary world. A house with modern siding lurks in the background too, but the blade is ornate, giving the modern setting a ritual gravity. The prairie flowers are resonant with the Solar symbolism in the Strength card, despite the darker content.

The image is provocative and open. Is this a show of strength because she is killing an animal to feed herself and her family? Or is this an example of strength because she is showing mercy to an animal by killing it? Perhaps the fawn is sick or fatally injured and the woman is doing something violent out of a feeling of deep compassion. Or perhaps you see it the way some angry Twitter users saw it, which is that the artist is saying it is a show of brute strength to kill another being. However you see it, it likely reflects your attitudes towards life and death.

When we look into the mirror of nature, we don’t see an objective truth. Instead, the information that we take in through the senses merges with our memories, insecurities, moods, and desires. Our inner-world and outer-world meet to form the image that we see.

Our ego, unconscious, and complexes reflect off of the mirror. Where some see a young woman committing an act of mercy in Wagner’s Strength, others will see a monstrous image that should be reported and removed. Wagner’s image confronts us with the question of how killing can be an expression of strength.

Nature is full of death and decay. There is no life without death. But more importantly, there is no living without participating in the cycle of life and death. You too are an animal. You too must establish your habitat at the cost of the frogs, birds, and beasts that once dwelled in the trees and grasses that were plowed for the foundation and the lumber of your home.

The controversial truth that I am hoping to communicate in this essay is that the people who see themselves as standing outside and above the cycle of life are more dangerous than those who can accept their place within it. This not only includes those who clear-cut ancient forests, but many animal activists who cannot come to terms with the cost of being an animal on this planet.

I argue that there is a need for adults to come to terms with the fact that your life comes at a cost. Growing up requires looking into the mirror of nature and seeing ourselves reflected back in the things we once denied. You are not just the hunter or the fawn. You are both. Recognizing this will bring us out of a comfortable dissociation and put us in touch with hard truths; that we all will die, that our life depends on the death of other life-forms, and that we are deeply interdependent with plants, animals, bacteria, bodies of water, and larger systems.

And this lesson goes beyond our relationship with more-than-human nature. When someone reacts so strongly to an image that they imagine monsters, there is a good chance they are projecting a shadow (the part of ourselves that we refuse to acknowledge). There is a good chance that this behavior impacts the way they see and treat other humans.

To some, what I am saying might seem like a paradox. But life teaches hard lessons about strength and compassion whether or not we are open to them. I have seen people leave animals to slowly die in a trap that they set because they did not have the strength to kill it themselves. When someone cannot kill the animal in their trap, they often see it as their own empathy getting in the way. But this is the shadow at work. There is a fear about one’s identity as good. Strength might mean doing the hard thing. It might mean having dirty hands.

What follows is a reflection on nature, mirrors, and shadows.

Nature is a mirror. And like all mirrors, what we see is not a simple reflection of reality. Body dysmorphia can cause us to see defects and proportions that are not really there. Noses grow, stomachs swell, and muscles shrivel. What is seen is a reflection of one’s affective experience.

Teenagers especially project insecurities onto their own reflections due to the adolescent stage of development which must create a cohesive self-image out of the internal and environmental data available. But adults also negotiate their reflections based on interpersonal and environmental experiences. Even in healthy adults, our perception is heavily influenced by our values, cultural background, environment, and emotional state.

The mirror symbol in myths and stories often has some kind of agency or uncertainty. In the scene of Galadriel’s mirror in the Lord of the Rings movies, Frodo asks “What will I see?” Galadriel responds “Even the wisest cannot tell.” The mirror seems to reflect fears and life tasks of the looker. This speaks to the intra-action of the the person and mirror.1

Of course, it is not just nature that we project onto, and the idea that we project our inner-lives onto the world around us is certainly not new. Many therapists are quick to point out that our reactions to others are often messages to ourselves about parts of ourselves that we reject.

But nature serves as a particularly powerful mirror. Earth-based traditions understand this and include nature observation in growth-oriented traditions. For example, Lakota culture (among many others) uses the vision quest as a rite of passage where individuals spend solitary time in a natural setting. People come to see themselves in new ways through the experience. Participants may receive a new name, a life mission, or an animal which they come to relate to. This is a meeting between the inner and outer world.

Mirrors in stories often show a confrontation with a person’s shadow.

As in the case of The Black Swan, pictured above, there is a gap between the character and her reflection. But the distortion is what allows the character to see a part of herself.

The mirror scenes are not representative of a character’s first time seeing a mirror. But they do represent the character’s first time seeing their shadow. When Natalie Portman’s character sees the darker character in the mirror, it is not the first time she has looked in the mirror. It is a change in the character’s relationship to the mirror. In other words, our interactions with mirrors come in stages.

As young people, we are supposed to project onto the world with little awareness. We see the world around us with a heavy filter of our own experiences. As the Jungian analyst and author James Hollis put it, “Inescapably, the first half of life is lived amid the massive unconsciousness of youth; but central to the suffering which arrives at midlife is a necessary accounting of what we have done to others and to ourselves” (Hollis, 1996, pg 33).2

Notice that Hollis uses the words “massive unconsciousness” to describe youth. It is not a claim that youthfulness is unhealthy or pathological, but that it is limited in the layers of critical reflection that mature adulthood requires. Further, Hollis contrasts this with an accounting of “what we have done to others and to ourselves.” This is a heavy theme, but one that fits the mirror symbol where one’s reflection begins to change in ways that one is disturbed by.

That change is the ability to start to see in ourselves what we would have previously projected onto beings outside of ourselves. It is letting go of childish (and dangerous) notions like “purity” or simple binaries. And it is a welcoming of responsibility.

But the integration of the shadow can bog us down. What should be a transitionary stage can become a swamp that pulls us under and keeps us. If we don’t have community, support, and courage, we risk losing our way and remaining in the swamp. The swamp is full of medicines like guilt and grief, but the difference between medicine and poison is a matter of dosage (more about that in part 2).

The Shadow (and Nature)

In nature, the wolf often serves as the bearer of man’s projections. There are numerous histories and theories of cultural hatred of the wolf (Safina, 2015; Lopez, 1978; Blakeslee, 2018; and Van Horn, 2012)3, but many point out that this religious-level hatred does not seem to be explainable through the threat to livestock alone. Wolves have rarely killed humans, and account for a tiny percentage of livestock deaths. Furthermore, the hatred of wolves takes on superstitious and epic proportions. Not only do fake stories circulate for the justifications of killing wolves, but the slaughter and torture of wolves hints that a shadow projection is at work.

In European-American culture, as well as many others around the world, wolves have been associated with devils, wilderness, sin, and evil. Instead of simply being shot, they have been burned at the stake, dragged behind vehicles, slowly tortured to death, and been hung up to display their gruesome manner of killing. Even in our contemporary setting, people around the world post videos of themselves torturing wolves while laughing.

I am not the first person to point out that the cultural experience of hating wolves cannot be explained through the loss of livestock alone and must lie deeper in man’s psychology. (Jesse, 2000; Lopez, 1978)4.

As Kirk Robinson (2019)5 points out, the wolf is an easy target of our projections because of its similarities to us. Both humans and wolves are highly social, land-based predators with body language that makes it easier for us to empathize with and therefore project onto. While there was once a mutualism between humans and wolves, humans began to create sedentary civilization with a growing cultural dualism between civilization and the wild. Humans rejected their wildness while wolves became a symbol of the wilderness to Western humans. Robinson makes an interesting point that people love dogs while hating wolves, and that our hatred of wolves may be a projection of our fear of our wild selves. Despite their species overlap, dogs remain on the “civilized” side of this cultural divide. They are controlled and appropriately groomed and tamed.

The rhetoric coming from those who kill and torture wolves is that the wolf is evil. The wolf functions as a scapegoat. It carries the sins of those who kill it. The wolf hunts through deception they say, while they set traps for it. It is beastly, they say while they drag its broken body behind a vehicle. The wolf kills cattle, they say while enclosing thousands of cattle behind fences to be slaughtered for profit.

On the other side of the spectrum from the wolf hunters are those who imagine a pure world of nature with humans as saviors. For example, I recently received some angry comments about a fishing video that I shared. The large fish remained on a hook and some commenters referred to it as torture and said that the humans in the video deserved to die. The fish, on the other hand, was “innocent.”

But the particular species of fish in question was a very large predator. It would need to kill and eat thousands of other fish to reach that size. This devourer of fish maintained its innocence in the eyes of the angry commenters while the same behavior in the fishermen was deserving of a death sentence. Clearly, this was human/nature dualism at work. For how could killing fish be innocent and monstrous at the same time unless humans are separate and above the rest of animals? At the least, this perspective of the innocent fish and monstrous humans implies that fish are innocent because they aren’t on a level with humans.

Cartesian dualism, the philosophy that explicitly separates humans from the rest of nature, has encouraged and justified the poisoning of rivers, industrial trawling of the oceans, clear-cutting of ancient forests, and mass extinction of species. In fact, Descartes himself justified the abuse of animals in experiments by claiming that since they did not have minds like humans, they could not feel pain. But many animal activists operate with this same orientation to nature and wildlife. The rhetoric of the innocent predator-fish and the fishermen who deserve to die shows these commenters’ firm faith in their own separation from nature. And I would argue that the anti-animal Cartesian dualism and the pro-animal dualism of animal activists arrive at the same wasteland of destroyed ecosystems because of their need to see nature on their own terms.

Even university professors have proposed the removal of predation in the wild to avoid the suffering of prey species (McMahan, 2014; Nussbaum, 2006).6 The obvious rebuttal to such ideas has been that removing predators from the wild cannot be done without causing harm to ecosystems and increasing the suffering of all species by removing limits to overgrazing and other habitat altering behaviors.7

Thus, those who hate hunting and those who hate wolves are often operating out of the same orientation to nature. The wolf-hunter projects the wild within himself onto the wolf and wants to eliminate it. The anti-predation advocates see the darker side of nature and cannot accept it. They refuse to see themselves in the cycle of life and death.

The pro-animal dualist refuses to see, and therefore cannot take responsibility for, that their house was once trees, their technologies destroy habitats, and their cat is fed with beef from a factory farm. Even a diet of only vegetables requires acres of deforestation to feed a human. Instead of the complex and nuanced world of nature, they see arbitrary separations everywhere.

This brings us back to the image of the woman holding a knife to the fawn. Why was the image called Strength? I imagine the people who hated that image have a lot in common with the professors who would eliminate predators from the wild and feed lions vegetarian diets. But in reality, this kind of thinking is the avoidance of guilt, rather than the elimination of suffering.

The ones who deny that animals have inner experiences and the ones who want to protect them from all harm both create wastelands. They each profess to love nature but only if it is on their terms. Their inability to experience discomfort becomes everyone else’s problem.

In Lion King, Scar’s sense of victimhood leads to setting up a kingdom where his own discomfort is assuaged. In doing so, a wasteland is created.

There is more at stake than just conservation issues. The failure to integrate one’s shadows and come to terms with the inherent loss and death in life impacts our human relationships and social institutions.

There is no more dangerous force in modern history than the nation with a victim complex. The victim complex and the shadow projection has preceded acts of unthinkable and systematic cruelty. The narration of one’s own victimhood becomes an unshakable deflection of their own guilt. And on an individual level, the person who starts to imagine monsters is ready to justify any behavior under the pretense of their own safety or saving someone else.

Just as the Karpman drama triangle8 suggests the role of the victim can fluctuate between victim, rescuer, and persecutor. The rescuer is often compelled by the need to disguise their own shadows in the concern for others. Of course, the willingness to help others in need is important and not always bad. But it is the rescuer’s lack of self-awareness that makes their efforts damaging.

Coming to terms with one’s own shadow is not demobilizing. Instead, it enables us to act out of sincere care. It enables us to care for the world as a part of it. It enables us to approach people who are behaving destructively as an equal, rather than their superior.

The protection of wildlife remains one of the most important causes in my own worldview. But I believe that a more wholistic understanding of life shows that sensitivity has its strengths and weakness. Sensitivity is important for us to care for ourselves and others. But our inability to sit with discomfort and pain can lead us to interventions that are more about ourselves and our desire to establish control, rather than sincere care for others. Discernment to know the difference comes from looking into the mirror of nature.

I do not propose that we kill fawns or hunt wolves. I do not advocate for any particular diet. But I do advocate for seeing ourselves in nature; to know that we are animals and, therefore, not separate or above the other species on Earth. And I think being honest that we too will cause harm or expire life in our own pursuit of living means that we can more effective in our commitments to protecting life.

I believe we desperately need rites of passage and initiations. We need our journeys into the wild. We need our elders who embrace their continued growth rather than clinging to youth. We need someone to show us the mirror of nature until it ripples and changes before our eyes. The initiation shows the hunter that what he hates in the wolf is what he fears in himself. The elder shows the anti-predation advocate their reflection in the girl who kills the fawn.

These initiations and the immersion in wild places teach us things about life. The lessons hurt but they give us meaning and enchant our vision.

The last form of guilt is existential in character; it is an unavoidable concomitant of being human. For example, we understand that the principle which underlies life is death. Not only are life and death the systole and diastole of the cosmos, but all life depends on killing. We kill animals to survive. If we choose to be vegetarian, we slay plant life. If we stop eating we commit suicide. For this reason our ancestors offered ‘grace’ at meals, that is not only thanks but the acknowledgement of the principle that what we are about to eat has derived from an act of slaying. Ancient cultures, for the same reason, offered prayers before and after the hunt and during consumption of the food, in order to acknowledge their participation in the death-rebirth cycle of the Great Mother archetype.”

James Hollis, Swamplands of the Soul (1996).

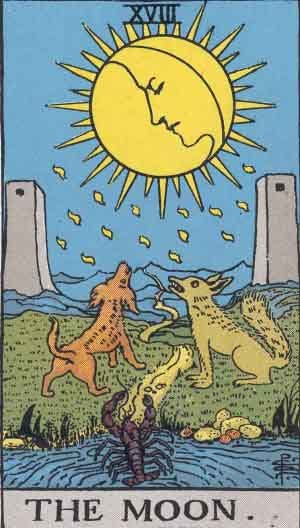

Robinson’s insight of the dog as a representation of our identity as civilized people trying to separate ourselves from our animal nature echoes the themes of the moon card in the classic tarot cards.

The image shows a path between two towers. A dog and a wolf are on either side of the path looking up at the moon, perhaps howling. The dog is groomed with golden fur, and the wolf is bushy and gray with sharp teeth. The water and the lobster symbolize the emotional and intuitive side of our psyche, which hints that the card sees the wolf as something to integrate rather than separate.

This path is the one we take through earth-based initiations. It is what nature teaches us. I hope to expand on that in the following essays.

We are the hunter and the hunted. The civilized and the wild.

Intra-action is a term used by Karen Barad to describe the dynamism of forces that perform actions. Intra-action removes the Cartesian dualism implied in the neat categories of subject and object and sees an intra-action of the observer and observed.

James Hollis, Swamplands of the Soul: New Life in Dismal Places. 1996.

Carl Safina, Beyond Words: How Animals Think and Feel. 2015; Barry Lopez, Of Wolves and Men. 1978; Nate Blakeslee American Wolf: A True Story of Survival and and Obsession in the West. 2018; Gavin Van Horn The Making of a Wilderness Icon in Animals and the Human Imagination. 2012.

Barry Lopez, Of Wolves and Men. 1978; Jesse, Wolves in Western Literature. 2000. (Chancelor’s Honors Program Projects).

Kirk Robinson, The Psychology of Wolf Fear and Loathing. 2019.

Jeffrey McMahan, The Moral Problem of Predation. 2014; Martha Nussbaum, Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. 2006.

Alan Vincelette, In Defense of Tigers and Wolves. (2022).

Lynne Forest, The Three Faces of Victim: An Overview of the Drama Triangle. 2008.

Bradley, this was so very timely for my own personal reflection in nature around pains and rage sparked from a recent tragedy involving a man and a wolf. Thank you for tempering these fires with the cool waters of reflection.

This is so insightful.